Between intellect and artistry

Toward a moral stance on where life should be lived

When a writer sits down to write, it’s best not to assume what will be revealed through the process. The writer who believes they’ll have anything close to the full picture when the work is done is obstinate and would be best letting ChatGPT do the work. This is probably true for all pursuits; the spirit of inquiry is what leaves the door open for any pursuit to be moral: to be between intellectual and artistic.

Creatives who live between intellect and artistry must accept that they pursue truth through thought, form, reason, and resonance - and hard lines don’t always need to be drawn. This is the place creatives should be. Cliche as it sounds, modern creatives must be satisfied by the pursuit, perpetuating what John Keats called the negative capability of poets. The pursuit requires integration of many things and an acceptance that knowing and feeling are not separate faculties but the two halves of inquiry.

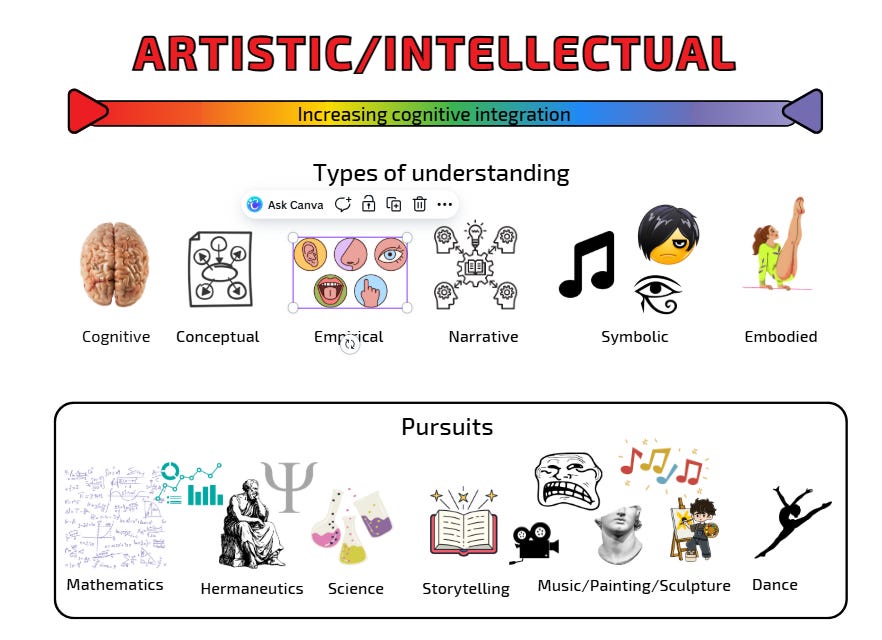

It’s not to say that a general shape of an idea can’t be cast or even refined, but that we accept limitations and error. If intellectual and artistic pursuits were to be spread on a spectrum, one might imagine one end holding the most rigid cognitive systems, (abstract logic, mathematics, etc) and the other, the most embodied systems. I’d argue that integration of the two occurs on another plane, creating “a special third (nth) thing” where the two ends are appreciated and held both separate and together. Integrated. I can’t fully explain it now (or probably ever), and inevitably I’m at least somewhat wrong, but it’s the pursuit of this idea that drives me.

Artistic and intellectual pursuits are not opposites, but complementary modes of inquiry, mediated by a desire to connect with reality. Deep understanding requires integration of both. The artist must think and the intellectual must feel, and the tension is where the truth is found. The seeming dichotomy between openness and control is not a challenge to be overcome or reduced, but a critical aspect of truth itself.

Writing appears as the most intellectual of the artistic pursuits, but only because it can use systematized symbols to (partially) disassemble whatever feeling it began in. Beneath syntax and structure lies the same intuitive pulse that drives painting or music. Intellectuals must accept that they have an embodied urge to translate sensation into meaning, and in doing so, they can go too far. See early Ludwig Wittgenstein.

The writer’s mind may appear analytical, parsing thought into grammar and argument, but what animates each word is affect. Even the densest technical jargon carries the purveyors’ ache for knowledge in every overarticulated procedure. We fold yearning into discovery every time we neologize. We can’t help but synthesize. Writing, even that of a scientist, is not a pure distillation of intellect but a choreography of thought and feeling, attempting to sweep away its visceral origins in the structure of reason.

We’ve tried to chalk up the two pursuits like this:

Art is felt. Embodied.

Intellect is thought. Reasoned.

But one requires the other. The artist must have the cognitive ability to inquire, to devote oneself to pursuit, and to hone a set of skills that allow precise exploration. The intellectual must develop a “sense” for logic. The click of sensemaking occurs when they feel they have made contact with reality, despite having no objective way of knowing they have.

Too much intellect sterilizes feeling, and too much artistry releases coherence. Synthesis is the highest form of inquiry. And as a curious species, it is our duty to inquire.

Some of the greatest artists and intellectuals have issued similar statements. The composer Richard Wagner believed that drama was the highest form of art because of its capacity for synthesis. In The Artwork of the Future, Wagner finds the dancer, tone artist, and poet to be one in the same:

“…Artistic Man who in the fullest measure of his faculties imparts himself to the highest expression of receptive power”.

While Wagner recommends integration of artistic pursuits, others have integrated more cognitive work with emotional work. Neuroscientist and artist Ramon y Cajal believed that scientific pursuit required integration of the passions:

“It is not sufficient to examine; it is also necessary to observe and reflect: we should infuse the things we observe with the intensity of our emotions and with a deep sense of affinity. We should make them our own where the heart is concerned, as well as in an intellectual sense. Only then will they surrender their secrets to us, for enthusiasm heightens and refines our perception. As with the lover who discovers new perfections every day in the woman he adores, he who studies an object with an endless sense of pleasure finally discerns interesting details and unusual properties that escape the thoughtless attention of those who work in a routine way.”

Art expresses its paradox more readily to us than does the purely intellectual pursuit, likely because, in our hubris, we resist the notion that we can’t completely understand something. In Aesthetic Theory, Theodor Adorno intentionally and demonstratively rambles about how art eludes us as we try to wrap our minds around it, capturing what he calls its enigmaticalness.

“That artworks say something and in the same breath conceal it expresses this enigmaticalness from the perspective of language.”

He thinks this perspective of understanding art through language demonstrates “clownish” cavorting of art. From within the artwork, this paradox disappears. It feels coherent and complete, but once we step outside with the attempt to find the Archimedian point, explaining, measuring, rationalizing, the paradox “returns like a spirit”, exposing the limits of intellect before the sensuous and the symbolic. This tension is where the divide between artistic and intellectual pursuits becomes visible, with intellect demanding clarity and art insisting on mystery.

We struggle with this as contemporary society is largely beholden to science. Almost half of the EU and one-third of the US work in a science or technological field. Even if we aren’t trained in scientific experimentation professionally, we’re trained to believe that scientific experimentation will answer inquiry. And it does sufficiently answer many inquiries, but not all. And this vexes us.

This vexes me. As a scientist, for many years, the artwork’s refusal to justify itself felt like a provocation. But as I let the idea in slowly through reading increasingly more enigmatical philosophy and metaphor, that very alienness, the inability to reduce art to sense or statement, confirms a kind of truth that I’ve always known: some forms of knowing can only be felt.

Despite our efforts, we scientists are unable to remove our feelings from our work. In school, the goal seemed to be to become the most accurate and precise data generation machine. Our program director would sneak up on people in the lab while they were pipetting (me) and then chastise us (me) for having a startle response. “It means you’re thinking about something you’re not supposed to be thinking about. Focus on your experiment!” I’m still not sure if he was joking, but to remedy the error, I made a Spock-like attempt to remove my sense of humor anyway. It was only recently, when I allowed myself to “waste time” watching the whole Star Trek series, that I realized Spock would not be as effective as he’s portrayed without being affective.

Kirk is the captain because, while he leads with intuition, he can integrate logic.

Inquiry seeks an answer, but doesn’t demand it. Science and intellectual pursuits look for empirical validation or frameworks to test things against. Art seeks validation internally (when done well), but the irony is that both artistic and intellectual impulses, when followed honestly, can be the most invalidating things one can devote oneself to. It’s absurd and impossible, but to that end, devoting oneself to inquiry might just be the moral compass someone like me needs.

To explore this idea further, I’m excited to announce that we’ll be kicking off our 2026 book club with Agnes Callard’s brand of neo-Socratic ethics in Open Socrates (Preview the list - finalized version coming soon).

I’d even be willing to build on this argument and stake a claim that the most ontologically grounded form of inquiry requires both art and intellect to make out the general shape of reality.

Not that I think we can, but we will try.

And not that I think I will ever formally publish on this, but here we are.

This is what it means to live in the absurd space between intellect and artistry. There’s no hope of mastery, but only of continual learning. The work isn’t to resolve the tension between letting curiosity think and thinking feel, to dissolve inside the enigma and precipitate back out - forever oscillating.

Week 34 Thought Experiment: Kirk Mode, Spock Mode

I did a little experiment on myself today.

I wrote my morning pages while holding a few stretches on the floor. Then I tried to notice whether I was in Kirk mode or Spock mode.

Immediately, I felt Kirkian: impulsive, alive, embodied. But then I tried to test it by switching. What would Spock do?

He would use sensory perception to answer the inquiry.

I was certainly embodied: in a pancake stretch, bobbing my head to Never Catch Me by Flying Lotus and Kendrick Lamar.

You try.

Which mode are you in now?

Questions to Ask Yourself

What’s your body doing?

What happens when you notice it?

If you can’t think, notice what happens when you slow down.

Close your eyes and take ten of the deepest, longest breaths you can muster.

What’s your first instinct to figure this out? Do you need to write it out?

Once I was in Spock mode, I started to think about how I felt, turning the inquiry back on itself.

I felt 2 parts satisfaction with my ability to figure this out, and 1 part worry that I was turning emotion into data - really more so what it might mean if this became a categorical imperative we all had to live under.

I had to stop myself to consider what SuperSpock mode might look like. SuperSpock lives with the contradiction of things. He integrates. He oscillates and switches, and challenges his position, but also enjoys it.

I’ve written about this before a few times. Here. And chatted about it.

Also about embodiment/phenomenology/intuition.

As you know, I’ll probably never be done writing about this.

I think I'm locked into a permanent, Chekovian, "WTF did you just say, Captain?" mode...

It's always a balance between what should and shouldn't be focused on for sure. People have called some of my fiction work a "philosophy text book in narrative form". It's not easy to balance.