Negative Nancy

Why most of us aren't genuine PollyAnnas

Subscribe for the freshest takes on the interwebs.

Negativity bias is a bitch. It’s the human tendency to register negative stimuli at the drop of a dime. It’s what beckons us to ruminate on negative events.

It gets me all the time, but not today — so I’d like to take a minute to observe it. I tend to thought spiral downward pretty quickly, so I’m trying to reconstruct the thought spiral upward in a feeble attempt to replicate it and avoid the pitfalls of negativity bias. Maybe if we understand what the bias is, we might be able to watch out for it.

Research suggests there are 4 components of negativity bias1:

Negative potency: Negative events are stronger than positive

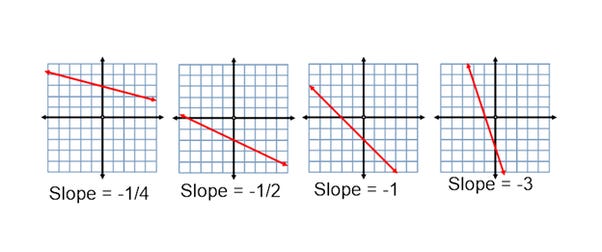

Negative gradients: Negativity can ramp up quicker than positivity

Negativity dominance: Negative and positive events do not balance each other out.

Negative differentiation: Negativity is more variable & complex than positivity

Potency:

Daniel Kahneman describes this in his studies of heuristics when it comes to loss aversion. In short, it’s why it feels better to not lose $50 than to get $50. The potency of the negative event is greater even though the magnitude is the same. Thinking Fast and Slow is an excellent compilation of Kahneman’s work, if you’re interested in analyzing why we do what we do.

Steep negativity gradient:

Experiments in animals and humans demonstrate that negative stimuli build up quicker than positive ones. A variety of experiments have been done with foot shock aversive tests in rats as well as perception-based experiments in humans. It doesn’t take a lot to produce a negative result quickly, but incentivizing a positive response is more difficult. The metaphor of rolling a boulder downhill, compared to pushing it up, is very fitting here.

Negativity dominance:

Potency and dominance are similar, but you wouldn’t eat a bowl of Cocoa Puffs if there were a 1:40 ratio of dog kibble mixed in. This is an example of dominance. Another would be if losing $100 was as bad as winning $150 was good.

Negative differentiation:

There is substantial evidence that the way perceive and react to negative stimuli is quite complex and differentiated. Another way negativity bias manifests is through language. There is a richness in the vocabulary used to describe pain, that simply isn’t seen for pleasure. Perhaps there is some causal link between this and the fact that people seek more explanations for negative events than positive ones.

Of course, there are instances that lead to positivity bias, and not everyone experiences the same extent of these biases.

What can we do to thwart our own bias?

There’s a growing body of evidence that mindfulness2 can help ward off negativity bias and possibly even increase positive judgments. A wide range of cognitive programs such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Acceptance Commitment Therapy show promise for combatting negative stimuli - helping us “unfuse” from negative thoughts and patterns.

Personally, I try to practice outward mindfulness when I can. When I feel a strong negative response, I *try* to pull back, rather than react outwardly, to examine my response. I also have an array of techniques to help me release negativity. It doesn’t always work, and it is a practice, but overall I feel better when I can successfully avoid a pit of negativity using skills that I’ve worked hard to gain.

I also tend to use humor to offset heavy topics and pain. This works for me, but outwardly, I can see when someone struggles with dark humor. It’s a sign that they’re in the thick of processing, or are still experiencing pain from it. So, dark humor can certainly offend and alienate.

We can be mindful and lighthearted in what we share, trying to counterbalance our negativity bias, but there is no silver bullet. It’s a human heuristic that we will continue to struggle with until it evolves out, or we find a better way to cope.

If all else fails, at least negativity fades with age3.

We feel pain, but not painlessness.... We feel the desire as we feel hunger and thirst; but as soon as it has been satisfied, it is like the mouthful of food which has been taken, and which ceases to exist for our feelings the moment it is swallowed.

-Arthur Schopenhauer

Rozin P and Royzman EB. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2001, Vol. 5, No. 4, 296-320

Kiken L and Shook Natalie Social Psychological and Personality Science 2011 2: 425

L Carstensen and DeLiema M Cur Op in Behav Sci Vol 19, 2018, Pages 7-12